To the “disappointment” of some but the delight of many the Girls’ Industrial Home, between Forest Hill pools and the library and popularly known as Louise House, was recently listed Grade II by English Heritage. The EH report noted the building’s historic and architectural interest, its association with several distinguished people and its value as part of a group of striking Victorian buildings.

To the “disappointment” of some but the delight of many the Girls’ Industrial Home, between Forest Hill pools and the library and popularly known as Louise House, was recently listed Grade II by English Heritage. The EH report noted the building’s historic and architectural interest, its association with several distinguished people and its value as part of a group of striking Victorian buildings.Industrial Homes developed from the Ragged School movement of the mid-19 century. These schools sought to give children a basic education and sufficient training to earn an honest living. However, it was believed that some children would only prosper if they were removed from the corrupting influence of their home environment; the industrial homes, often established in pleasant locations, provided that refuge; they were intended to be “home” for the children.

The first industrial home in Forest Hill, for boys, was opened in 1873 at 17 Rojack Road. In 1881 a girls’ home was opened at 16 Rojack Road. These two houses (which still survive) proved too small and in 1884 a purpose built boys’ industrial home, Shaftesbury House, Perry Rise, was opened by the Lord Mayor of London in the presence of the Earl of Shaftesbury, patron of the home. This building was needlessly demolished in 2000.

The four buildings fronting Dartmouth Road comprising Holy Trinity School, Forest Hill Library, Louise House (all three listed Grade II) and the pools were built within 25 years of each other and shared a common purpose, the welfare of less advantaged people in Forest Hill, Sydenham and beyond. They provided opportunities for education, religious instruction, exercise, cleanliness and training for a trade. Until fairly recently all four buildings were in use for the same, or very similar, purposes as those for which they were intended.

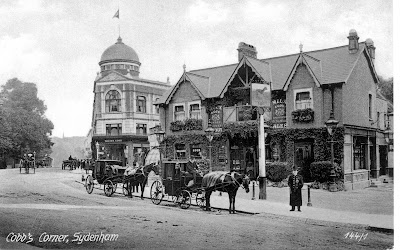

The history of the site began in 1819 when Sydenham Common (500 acres of open land in Upper Sydenham and Forest Hill) was enclosed. Since time immemorial the common had provided local people with certain rights such as free access, grazing livestock, gathering firewood, hunting and holding fairs. With enclosure the common was divided into small plots that were fenced to keep out trespassers. These plots were awarded to those who already owned land in Lewisham. Thus, as so often happens, the wealthy benefitted at the expense of the poor.

One of the beneficiaries was the Vicar of Lewisham who was awarded the large field on which these four buildings were to be erected. This field, known as Vicar’s Field, was originally let as allotments to those who had lost their common rights. As circumstances changed, the vicar (from 1854 the Vicar of St Bartholomew’s became the freeholder) was persuaded to make parts of this field available for purposes he deemed to be socially worthwhile. During the early 1870s Vicar’s Field was one of the sites proposed for a public recreation ground but the vicar decided such a use was not a good enough reason to deprive the poor of their allotments. An alternative site was found, now known as Mayow Park.

However, the vicar did agree to make part of the field available for a church school and in 1874 Holy Trinity School was opened. This was followed by the pools in 1885, Louise House in 1891 and finally the library in 1901.

Among local benefactors of the industrial homes FJ Horniman was one of the most generous as were several members of the Tetley family, Forest Hill’s other famous tea merchants. Princess Louise retained an interest in the building that bore her name.

Thomas Aldwinckle (1845-1920) was the principal architect of both the pools and Louise House. Although he built hospitals and workhouses across the south east (including Brook Hospital and the water tower on Shooters Hill, and the important Kentish Town baths) he was very much a local architect. He lived in Forest Hill for almost all his working life, at 1 Church Rise, Forest Hill from the mid-1870s until the mid-1880s and then at Saratoga, 62 Dacres Road until about 1908. His house in Dacres Road survives between Hennel Close and Catling Close, and was almost certainly designed by him.

Perhaps the most important person connected with Louise House was Janusz Korczak, a Polish Jew from Warsaw who wrote that he was inspired by a visit to Louise House in 1911 to found a similar institution in Poland. As a result of his experience at Louise House Korczak developed the idea that “the key to a happy and useful adult life lay in childhood; hurt the child and you hurt the adult.” He became an active campaigner for children’s rights which culminated in the Declaration of the Rights of the Child, later adopted by the United Nations. In 1942 Korczak, 12 members of his staff and 192 children at his orphanage were rounded up by the Nazis. Korczak was given the chance to escape but he would not abandon his children. The group was transported to the Treblinka extermination camp; that is the last that was heard of them.

Louise House remained a girls’ home (the word “Industrial” was carefully removed in about 1930) until the mid-1930s. By 1939 it was occupied by Air Raid Precautions and after the war it became a child welfare centre. Louise House was closed and boarded-up in 2005. The crèche in the laundry block at the back of Louise House, which continued the tradition of caring for young people, finally closed earlier this year after more than 25 years service.

Louise House is a rare survivor of a purpose built industrial home, made all the more important because it is largely intact, both inside and out. We are fortunate that its importance has been recognised and it has been saved for posterity.